RL Debate Series

Why do we have brains? Simple: to survive and reproduce. And neither is possible without some action. Therefore, brains are for generating behavior.

This puts action center stage in our quest toward intelligence. But how do we formalize active learning?

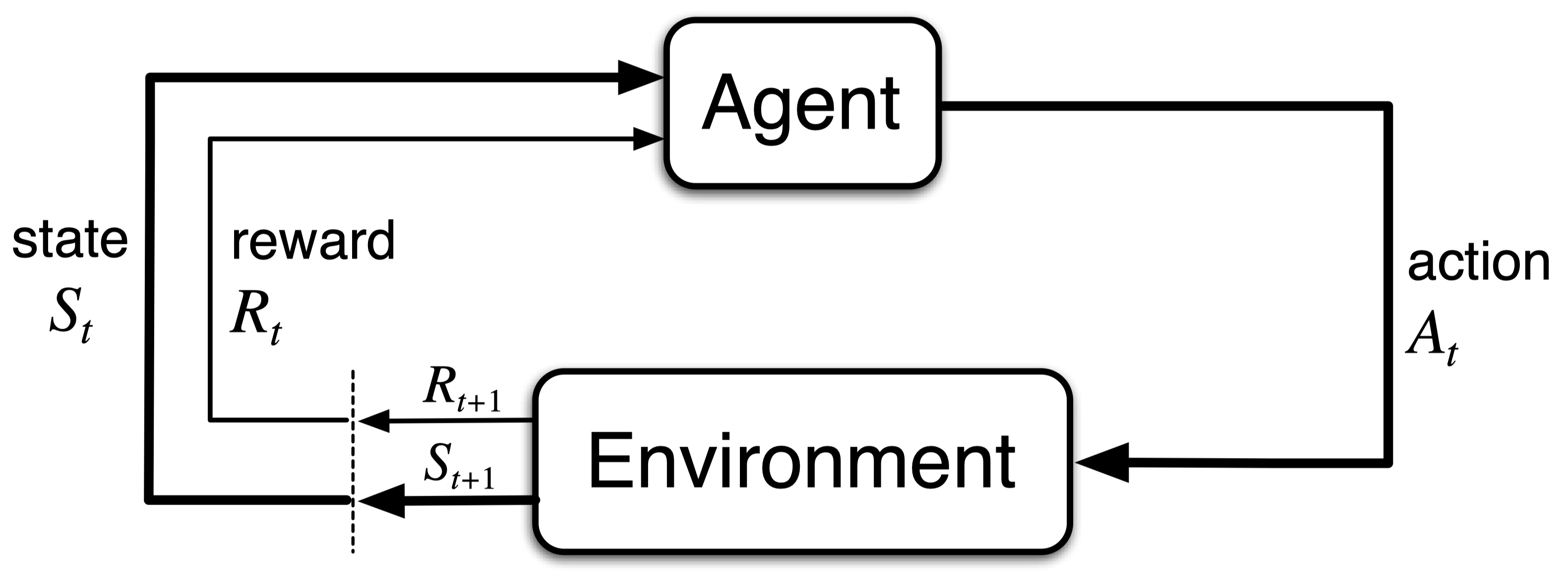

The mainstream approach here is reinforcement learning (RL), which posits that agents ‘act’ to maximize ‘rewards’. Consider this canonical figure from the Sutton & Barto textbook:

At each time step t, the agent produces action At, causing the environment’s state to evolve from St to St+1. The environment, in return, provides the agent with a scalar reward Rt+1. This summarizes the standard textbook view of active learning.

But RL faces fundamental challenges. To name a few:

- Rewards are inferred, not given.

- The scalar reward is ill-defined for complex behaviors.

- Not all active learning is reinforcement learning.

These issues motivate the need to upgrade—or even replace—RL as our go-to framework for active learning.

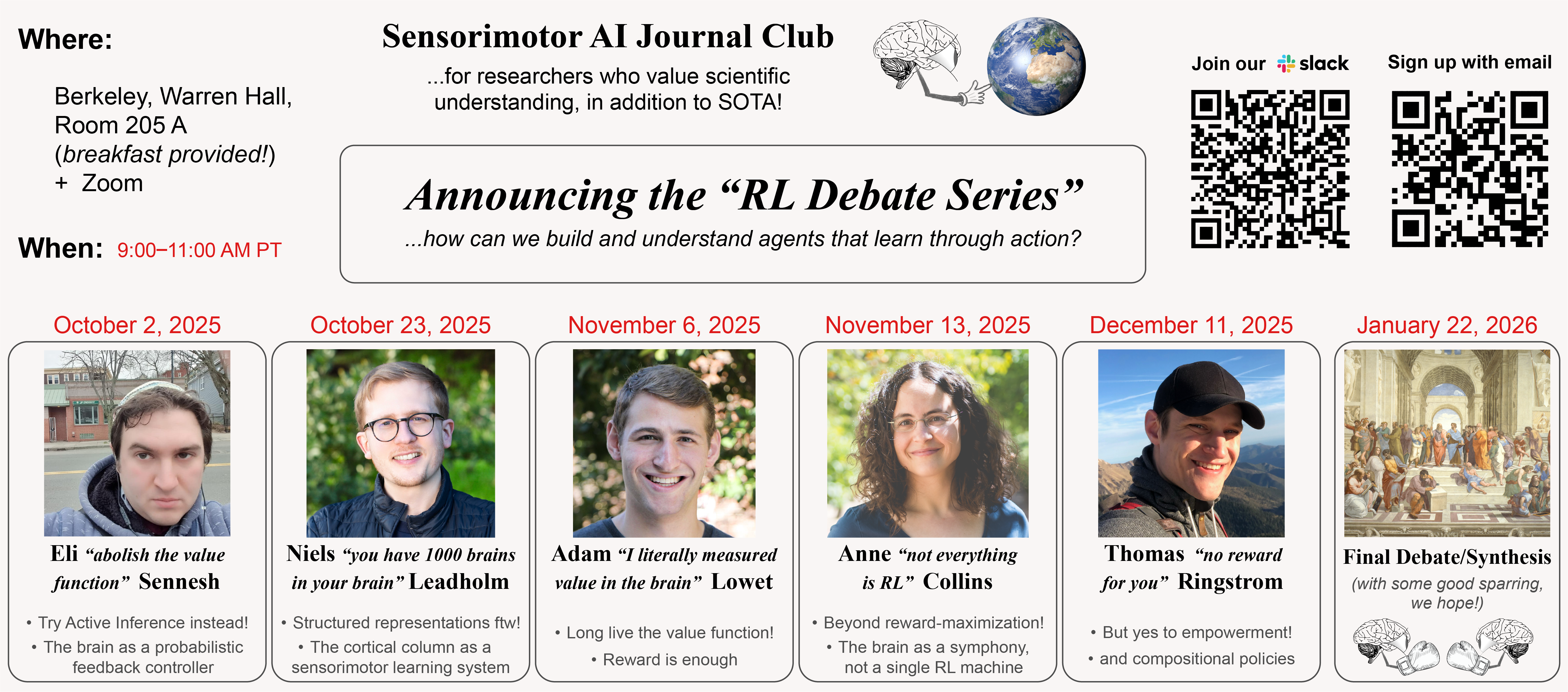

That’s why we’re launching the RL Debate Series, where researchers will defend and debate alternative theories of interactive learning and agency. See these introductory slides.

The first round: five presentations + final debate

Meet our five brave contenders, each ready to get in on the action and defend their favorite theory:

Appendix: shortcomings of mainstream RL

In this section, we substantiate the issues outlined above, reviewing conceptual, practical, and empirical challenges to mainstream RL that helped motivate our debate series.

(1) Rewards must be inferred, they are ultimately subjective

Imagine you’re a neuron, buried deep in the central nervous system of a human. From your perspective, there is no such thing as “outside world.” All that exists are spikes, or action potentials, arriving at your synapses from other neurons.

Everything else is inferred.

It’s the same with color: photons exist, color does not. Color is an inferred quantity, constructed by the brain from incoming sensory data.

Rewards work the same way (frankly, just like literally everything else). Rewards aren’t objective signals delivered by the environment. Rather, the brain must infer what is rewarding from sensory cues, filtered through its own subjective beliefs and preferences.

This is the first major problem with the Sutton & Barto view: the environment doesn’t hand out rewards. It provides sensory evidence that may or may not be interpreted as rewarding, depending on the agent.

(1.1) A concrete example: Burger vs. Salad

Consider two hungry people: one omnivore and one vegetarian. Put a double cheeseburger (with bacon) and a salad in front of them. Is there an objective, observer-independent scalar reward attached to each food? No. The omnivore finds the burger rewarding, the vegetarian the salad. Their choices reveal their internal preferences.

(Okay, maybe this is not the best example, because we all know the burger is objectively more rewarding. But this only shows how remarkably adaptive the human brain is: somehow a nervous system can trick itself into preferring salad over bacon… Incredible!)

To sum up, rewards are not given by the environment. Each agent must infer its own rewards from sensory data, shaped by subjective priors and internal states.

(2) RL typically works in toy settings where the reward is known

So far, the most celebrated successes of RL have come from toy domains: most famously Atari games, where the reward signal is dense, simple, and explicitly defined. But in the real world, we haven’t yet seen an agent succeed from “pure” RL alone. In robotics, for example, what actually works are still hand-engineered control systems, often carefully tuned by humans.

Even in neuroscience, the behaviors we study in the lab often rely on artificially simple rewards. Think of a rat pressing a lever for a drop of juice, or a mouse licking a spout for sugar water. These paradigms tell us something, but they don’t capture the messy richness of natural behavior.

Which brings us to the deeper question: is reward maximization really “enough” to model complex, real-world behaviors?

Consider a monk sitting in meditation for hours, seeking nothing but inner peace and serenity. What scalar environmental reward, exactly, is being maximized here? Or a child obsessively stacking blocks just to knock them down, over and over. What objective environmental reward is being dispensed in this case?

These cases highlight the problem: in complex environments, a single, externally defined reward signal may be ill-defined, insufficient, or even misleading as the basis of behavior.

(3) Not all active learning is reinforcement learning: a tale of Tolman’s rats

Finally, let’s revisit a classic experiment that showed not all active learning can be reduced to reinforcement learning.

In the early 20th century, behaviorism was dominant. Behaviorists weren’t interested in the brain, since they couldn’t measure it anyway. Instead, they studied only what was observable: stimuli in, behavior out. The brain was treated as a black box that mapped inputs (stimuli) to outputs (behavior). A famous example is Pavlov’s dog: you ring a bell (input stimulus), the dog salivates (output behavior).

But some rebels, like Edward Tolman at UC Berkeley, weren’t convinced. They argued that animals go beyond just stimulus-response reflexes, and build internal representations of the world that enable intelligent behavior. Tolman’s maze experiments offered compelling early evidence for this view.

(3.1) Experiment setup

Tolman and Honzik (1930) trained three groups of rats in a maze:

- Rewarded group: received food at the end of the maze every trial.

- No reward group: never received food reward.

- Delayed reward group: explored the maze without reward for the first 10 days, then received food from day 11 onward.

(3.2) Results

Performance was measured by error reduction, or how reliably the rats found the food by the end of each trial.

The ‘rewarded’ group had a slow but steady improvement in their performance. The ‘no reward’ group improved slightly, just from the experience of navigating.

The ‘delayed reward’ group was the most interesting: when they suddenly started receiving food, their performance spiked. They quickly caught up to, and even outperformed, the consistently rewarded group.

Tolman called this latent learning: the rats had built an internal cognitive map of the maze without explicit rewards. Crucially:

- Rats demonstrated active learning without any well-defined reward from the environment.

- Continuous external rewards actually interfered with this ability: the delayed group learned more efficiently once a reward appeared.

- The delayed group was exploring freely, showing clear evidence for active learning. But importantly, it wasn’t reinforcement learning in the Sutton & Barto sense.

(3.3) Two possible interpretations

This finding can be read in two ways:

- Reward is NOT enough: We may need to upgrade or replace RL with a framework that isn’t solely reward-based.

- Intrinsic motivation: Maybe learning is driven by curiosity, exploration, or other intrinsic signals. What if exploration and curiosity are simply additional scalar rewards?

This interpretation sounds like a convenient patch, but it leads to a critical logical inconsistency: if intrinsic motivation is truly “intrinsic,” it must originate within the agent itself, not be delivered by the environment as the Sutton & Barto diagram suggests. Therefore, this attempt would break the fundamental assumption that rewards come from the environment.

To summarize, Tolman’s rats showed that animals can engage in sophisticated active learning—and even learn more efficiently—in the complete absence of environmental reward signals. Therefore, the very notion of a “reward provided by the environment” for active learning has been empirically contradicted since at least the 1930s (over six decades before Sutton & Barto wrote their book 🙂).

Final remarks

There you have it, folks. Three glaring issues with the Sutton & Barto view of RL. It makes you wonder… what if we haven’t solved agency, not because it’s too hard, but because we’ve been using the wrong theoretical framework all along?

Join our RL Debate Series, and together, we may find a way forward.

Hadi (on behalf of the Sensorimotor AI Journal Club)